- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Dr Sudhir Kumar Das

(The writer can be reached at dasudhirk@gmail.com)

In an age of post-truth, history has been reduced to a narrative befitting an ideological framework. In order to claim objectivity, selective historical facts are highlighted by ideologically-driven historians, and facts countering that particular ideological narrative is either concealed or side-lined so that the desired narrative can be claimed as an objective analysis. As a result, we have now left-wing and right-wing historians and people have the choice to believe in what they like. British rule in India has been presented by many British historians as a civilizing process for the savage Indians. Whereas Indian nationalist historians highlight the barbaric brutalities natives were subjected to, the economic depredation of the native economy and the trampling of the native culture and language. In this conflicting ideological backdrop when one attempts to study the partition of India from an objective perspective it becomes as much difficult as trying to climb a high peak with a sprained ankle. There are several historical narratives of the partition of the Indian subcontinent; one is an Indian perspective, and the other two are Pakistani and British perspectives. Howsoever, the three different perspectives of the Partition may be, all the historians unequivocally agree that it remains one of the most painful chapters of world history perhaps second only to the extermination of Jews in Hitler's Germany.

An attempt to analyse the causes of the Partition of India can be traced, from an Indian perspective to three distinct strands of historical narrative. First, it was the intransigence of Mr Mohammad Ali Jinnah that resulted in the balkanization of India; second, the tacit support of the British for the demand for partition, instead of playing the role of a neutral umpire; third, Gandhi, the only person who could have stopped the partition of the country, played an ambiguous role giving away substantial political space to Jinnah in the crowded political canvas of that time.

Jinnah started his political career as a congressman in 1906 as a nationalist and communitarian. Many at that time considered him a symbol of Hindu-Muslim unity. In 1906 when the Muslim League was established, he had in fact opposed the formation of such a communal association. His transformation from a communitarian to a communalist began with the advent of Gandhi into the Congress Party. When Gandhi returned from South Africa in the year 1915 with a huge reputation following him as a leader of the masses fighting against the practice of apartheid there; his influence in the Congress Party grew rapidly. He took up the cases of common people of India one after another. He reinforced his image as a leader of the masses when he successfully led the Champaran Movement highlighting the plight of the exploited indigo farmers there. The growing stature of Gandhi in the Congress Party made Jinnah uncomfortable who never wanted to play second fiddle to anyone. Things came to head when in 1920 in the Nagpur convention of the Congress party Jinnah was shouted down by the members for not addressing Gandhi as 'Mahatma'. A miffed Jinnah left both the Muslim League and the Congress in 1920 and kept himself aloof from politics. He left for England and stayed in London from 1930 to 1935 practising law. Those five years were the period of his political hibernation. When under the Government of India Act (1935) provincial elections were to be held on the basis of a separate electorate; he returned to India to campaign for the Muslim League. But the results of the 1937 provincial elections were very discouraging as the Congress Party won an absolute majority in many provinces and even in Muslim majority Bengal and Punjab Muslim League failed to form a government. The failure in the 1937 elections made Jinnah a Muslim nationalist paving the way for him to demand a sovereign nation for the Muslims of India. He started talking in terms of "Hindus and Muslims were two different and distinct nations and could not become one political nation in a united India." He parroted this separatist idea in every single meeting of the Muslim League and in the Lahore Convention the AIML adopted the Pakistan Resolution on 23rd March 1940 demanding the Partition of India on the basis of religion into two separate sovereign nations out of the Muslim majority Bengal and Punjab. The Congress, on the other hand, was trying desperately to put up a united fight against the imperial British by presenting a united front claiming that it represents all Indians irrespective of caste, religion, race, and language. But Jinnah was bent upon sabotaging this façade of unity claimed by the Congress by insisting on the distinct cultural and religious differences between Hindus and Muslims. The INC tried hard to make Jinnah fall in line by dropping his demand for a partition of the country in return for political positions of authority in a united India. As late as April 1947, Gandhiji offered Jinnah an all-Muslim cabinet of ministers if he gave up his demand for Pakistan. Congress leaders like C Rajagopalachari offered Jinnah not only to nominate the Prime Ministerial candidate but also the cabinet of his choice. As Ayesha Jalal in her book The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (1985) writes that Jinnah wanted to be the sole and unchallenged leader of the Muslims in undivided India. But contrary to his claim, the INC usurped that position by declaring that they are the spokesman of all Indian irrespective of caste, race, religion, and language which irked Jinnah no end. To buttress their claim that they are the sole representatives of all Indians, including Muslims the Congress flaunted Abul Kalam Azad and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and some others as their Muslim faces. Jinnah termed them as traitors of the community. Moreover, Congress tried to keep the freedom movement secular but Jinnah was hell-bent on making the freedom struggle communal by raising the issue of Muslim separatism.

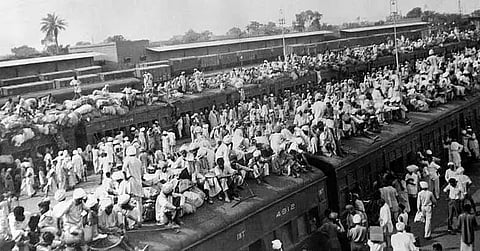

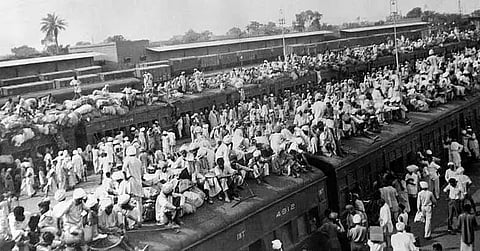

There are claims and counterclaims as to the role Jinnah played in the partition of India. Ishtiaq Ahmed, a Swedish professor emeritus of Political Science at Stockholm University and a man of Pakistani origin in his book Jinnah: His Successes, Failures, and Role in History (2019) holds the view that it was his intransigence to negotiate with Gandhi and the other Congress leaders brought about the catastrophe of Partition of India in which 14 million people were displaced and became refugees on both sides of the newly drawn border in blood and about a million got killed in the name of religion. All this just to satisfy the ego of just one person who did not want to accommodate any other political idea other than his own and was averse to playing second fiddle to anyone. However, a diametrically opposite view has been expressed by Jaswant Singh, the former Foreign Minister of India under Vajpayee, in his book Jinnah: India-Partition-Independence that it was not Jinnah but the centralized policy of Jawaharlal Nehru that left for no space any political manoeuvre for Jinnah and eventually he was forced to stick to his demand of partition. As mentioned earlier, it is an age of post-truth and one can believe in whichever narrative one wants to. (To be concluded)