- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Mita Nath

(mitanathbora7@gmail.com)

‘The train arrived from Lahore — no living passenger, only blood-soaked silence.’

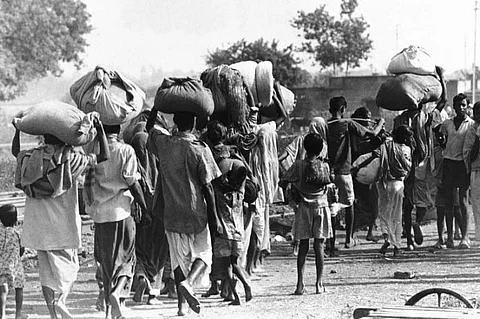

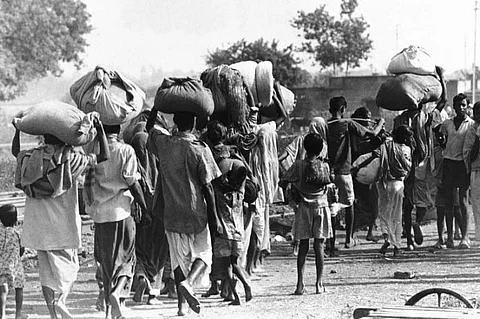

The 1947 Partition of India is often remembered through the triumphant lens of independence, but buried beneath the celebrations is one of the bloodiest and most haunting chapters in human history, a mass genocide that scarred the subcontinent forever. The image of trains arriving at stations carrying only corpses has become the most chilling symbol of that time. Those train sights and pictures still haunt citizens. They are reminders of humanity’s capacity for brutality.

When the British exited India, they left behind a hastily drawn line, the Radcliffe Line, dividing Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east on a religious basis and asked people to choose among the divided countries. Over 20 million people were displaced—Hindus and Sikhs moving eastward to India—but their journeys were anything but safe.

The British divided the nation but made no operational arrangement for transition and provided no safety or security provision as citizens were forced to move overnight. In fact, hatred and violence were let loose. It was not a peaceful transition but a cataclysm of communal hatred. What followed was confusion, chaos, mayhem, ethnic cleansing and widespread slaughter.

Trains, buses, and caravans were ambushed; women were raped; children were butchered and torched down to ashes; and families after families were erased. ‘Ghost Trains’ carrying refugees often pulled into stations with no survivors, only bloated, mutilated corpses, soaked in blood, stripped of dignity. Tracks were littered with bodies. Witnesses recount the smell of rot and the blood that pooled for days. Trains mostly became moving tombs, symbolizing the breakdown of humanity in the face of communal vengeance – funeral processions on iron wheels.

But the worst were the women who bore torture beyond words. The Partition was not only a political divide but also a moral collapse, especially in the way women were treated. Women became the most brutalised symbols of communal revenge, seen not as individuals but as representatives of enemy honour. Rape became a weapon, a tool to defile the Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist and Christian women who were abducted, raped, mutilated and killed. In several horrifying cases, foetuses were cut out of pregnant women, and their mutilated bodies were left on roads and trains as warnings. Their bodies bore witness to the collapse of all that was sacred—love, protection, motherhood, and dignity.

Historians estimate that over 75,000 to 100,000 women were abducted, raped, disfigured, and forcefully converted. Some were paraded naked; others were mutilated or killed after being dishonoured. This number includes documented cases, but the real figure may be much higher, hidden behind shame, silence, and fear, besides those killed and dug somewhere in lost land and those burnt alive and turned to ashes with no trace.

Many women jumped into wells to protect their honour. Others were killed by their own families in so-called ‘honour killings’. The systematic torture, sexual violence and human tragedy faced by women during the Partition of India can be felt by these real-life accounts that illustrate the depths of the horror.

Sohni (name changed), a teenage Hindu girl from Rawalpindi, was captured during the riots while her village was being set ablaze. She was dragged by a group of armed men, paraded naked in the marketplace, and locked in a room for over a week, where she was gang-raped repeatedly. Eventually, when the attackers grew tired of her, they poured kerosene over her and set her on fire. Sohni succumbed to her injuries. Her charred body was found later by Indian forces conducting a search operation. Her case became one of the first to be documented in the recovery efforts led by the Indian government.

In the village of Thoha Khalsa (Rawalpindi district), during March 1947, as Muslim mobs approached, 93 Sikh women jumped into a well to avoid being captured and dishonoured. They were told that if they were taken alive, they would be raped, forcibly converted, and sold off. This mass suicide is one of the most tragic examples of what families felt they had to do to protect ‘honour’, even if it meant killing their own daughters and wives. The haunting image of that well, full of lifeless bodies draped in tattered clothing, remains a searing reminder of the inhuman decisions imposed by Partition’s violence.

Nowhere in history were the horrors more visible than in the partition of India.

Post-Partition Governments initiated efforts to recover abducted women. Special officers were appointed, cross-border missions were launched, and hundreds of women were brought back. But many were already converted and forcibly married; many were pregnant with their rapists’ children and couldn’t return to families. Others could never trace their families back. And many were lost forever, erased from family memory and national history. Their stories are whispered only in family legends or buried under collective shame.

The Partition trauma wasn’t just about nations—it was about the women whose lives were stolen, who became the direct victims of hate. But they were not just victims; they were daughters, wives, sisters, and mothers made to bear a nation’s bloodstained birth alone.

While official records may shy away from the term ‘genocide’, the Partition massacres bore all the hallmarks of targeted killings based on religion, mass displacements and ethnic cleansing, systematic destruction of homes, places of worship, and cultural symbols, organized sexual violence and abductions. The scale of violence places the 1947 Partition of India among the largest genocides of the 20th century, alongside the Holocaust, the Rwandan Genocide and the Armenian massacre.

‘A Train Load of Dead Bodies’ is more than just a historical account; it’s a symbol of British colonial failure, of what happens when politics triumphs over people, and hatred drowns compassion.

As the subcontinent continues to battle Islamic terrorism, it must remember the Partition, not for revenge, but for reflection.

Let Us Remember

For the unnamed victims,

For the lost homes and burnt villages,

For the girls who never returned,

For the unborn who died in their mothers’ wombs—

We remember.