- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Dipak Kurmi

(The writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com.)

The grand narrative of India’s freedom struggle often finds its focal points in the political corridors of Calcutta, the industrial hubs of Bombay, the protests of Lahore, and the rallies of Delhi. Yet, in the mist-laden hills, lush valleys, and river-bound plains of Assam and the broader Northeast, another chapter was unfolding—a chapter where resistance was both fierce and quiet, where patriotism wore the faces of farmers, poets, tribal chiefs, students, and soldiers. This remote corner of India, connected to the rest of the country by the slender Siliguri Corridor, was never peripheral in spirit. Its people embraced the call for swaraj with an unwavering sense of belonging, weaving their struggles into the larger tapestry of India’s independence movement.

The story begins in 1826 with the Treaty of Yandaboo, which ended the First Anglo-Burmese War and marked the British annexation of Assam. For centuries before that, the Ahom kingdom had defended its independence against mighty adversaries. British rule dismantled this legacy, replacing traditional governance with exploitative revenue systems and transforming vast tracts of fertile land into tea plantations worked by indentured labour brought from central India. While the colonial administration hailed the tea industry as a symbol of progress, for thousands of Adivasi workers enduring harsh conditions, it became an emblem of bondage. These early experiences of displacement, economic exploitation, and cultural intrusion sowed seeds of resistance that would later blossom into organized political mobilisation.

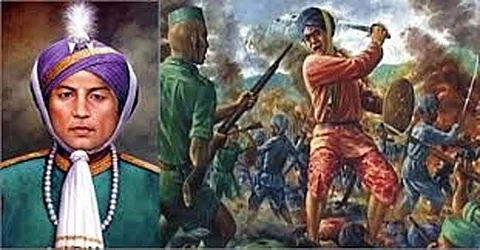

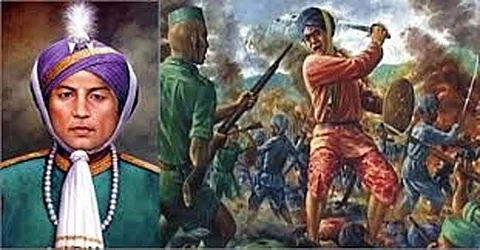

The first wave of defiance arose not in formal political assemblies but in acts of local courage. The revolt of 1857, known as the First War of Independence, reverberated in Assam through the heroism of Maniram Dewan and Piyali Barua. Maniram, one of the first Assamese entrepreneurs and a tea planter, had initially allied with the British but turned against them after witnessing their oppressive policies and disregard for local autonomy. His role in galvanizing discontent led to his arrest and execution in 1858, alongside the young revolutionary Piyali Barua. Their martyrdom became a beacon for future generations in the Brahmaputra valley, proving that resistance here was rooted in both economic grievances and a fierce pride in local identity.

By the late 19th century, Assam and parts of the Northeast began aligning with the larger currents of Indian nationalism. The Indian National Congress extended its influence into the region, finding fertile ground among leaders like Ambikagiri Raichoudhury, often called the “Lion of Assam”. His impassioned writings and speeches fused cultural revival with political activism, asserting Assam’s place in the national struggle while guarding its unique identity. The Swadeshi Movement of 1905, born in protest against the partition of Bengal, swept through Assam’s towns like Jorhat, Dibrugarh, and Guwahati. Students and traders shunned foreign goods, khadi looms clattered in homes, and women—often excluded from historical records—became custodians of this quiet revolution, turning households into hubs of political learning and defiance.

The tribal hills of the Northeast, though geographically distant from urban centres of protest, were not untouched by nationalist sentiment. In the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo hills, memories of earlier resistances against British intrusion—such as those led by Tirot Sing, U Tirot Sing Syiem, and Pa Togan Nengminja Sangma in the early 19th century—remained part of oral history and local pride. These movements, though predating the pan-Indian nationalist wave, were expressions of the same spirit: defence of land, culture, and self-rule.

The Non-Cooperation Movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi in 1920 found eager participants in Assam. Schools and colleges saw strikes; students abandoned British-run institutions in favour of national schools that promoted indigenous education. Leaders like Tarun Ram Phukan, Nabin Chandra Bardoloi, and Bishnuram Medhi brought together urban intelligentsia and rural farmers under a common banner. The British administration, alarmed by this groundswell of political consciousness, responded with arrests and repression, but the movement had already lit a fire that would not be extinguished.

The 1930s ushered in the Civil Disobedience Movement, and with it, the image of women as the vanguard of change became more visible. Figures like Kamala Miri, Pushpalata Das, and Chandraprabha Saikiani championed both political rights and social reform, particularly women’s education. Saikiani, a teacher turned activist, understood that the political liberation of the country was inseparable from the social emancipation of its people. Her speeches inspired many Assamese women to join the freedom struggle, challenging both colonial authority and patriarchal norms.

In the neighbouring hills and valleys, smaller but significant acts of defiance also unfolded. The Mizo Hills, Naga Hills, and Manipur—regions often seen as isolated—were strategic frontiers during the Second World War and thus became entwined with the Indian National Army’s (INA) campaigns. The INA, under Subhas Chandra Bose, sought to liberate India through armed struggle, and its march through Burma into the Northeast brought the war literally to Assam’s doorstep. The battles of Imphal and Kohima in 1944, though fought primarily in Manipur and Nagaland, had deep reverberations in Assam, bringing both devastation and a surge in anti-colonial sentiment. Many local youth were inspired by Bose’s call and lent support to the INA, whether through direct participation or by aiding in covert operations.

The Quit India Movement of 1942 became one of the most intense phases of Assam’s struggle. Across towns and villages, people defied curfews, picketed government offices, and disrupted communication lines. In Gohpur, the teenage Kanaklata Barua emerged as an enduring symbol of youthful courage. At just 18, she led a procession carrying the national flag and was shot dead by police. Her sacrifice, along with that of Mukunda Kakati and other martyrs, cemented the Quit India Movement’s place in Assam’s political consciousness.

While the armed and mass protests garnered attention, the intellectual and cultural resistance in Assam and the Northeast played an equally significant role. Writers and poets like Banikanta Kakati and Ambikagiri Raichoudhury used literature to challenge colonial narratives and instil pride in indigenous culture. Newspapers and journals became lifelines of the movement, carrying news, essays, and poems to far-flung corners despite censorship and the constant threat of suppression. In villages and small towns, theatre performances were crafted to embed nationalist ideals in local folklore, ensuring that the freedom movement was not just political but a cultural renaissance as well.

A distinctive feature of Assam’s role in the freedom struggle was its balancing act between nationalism and ethnic diversity. The state was, and remains, a mosaic of communities—Ahoms, Bodos, Karbis, Mishings, Adivasis, and others—each with its own language, customs, and aspirations. Leaders like Gopinath Bordoloi and Bishnuram Medhi recognised the importance of safeguarding indigenous rights while committing to the pan-Indian cause. Bordoloi’s deft political negotiations during the Cabinet Mission discussions ensured that Assam’s territorial integrity was preserved, preventing its tribal areas from being separated into a different administrative unit under British plans.

Elsewhere in the Northeast, the intertwining of local autonomy movements with the national struggle took varied forms. In Manipur, the women-led ‘Nupi Lal’ movements (1904 and 1939) against colonial economic exploitation and forced labour were powerful assertions of people’s rights. In Nagaland, early nationalist currents were cautious, as many communities prioritized local self-determination, yet the presence of nationalist ideas could not be ignored, especially during wartime. These distinct trajectories reflected the region’s complex relationship with the larger Indian nationalist project, but they also underscored a shared opposition to colonial exploitation.

As independence drew near, the people of Assam and the Northeast experienced a mix of jubilation and apprehension. The midnight of August 14–15, 1947, brought the tricolour to Guwahati, Shillong, Imphal, and Aizawl, but also the realities of partition. Assam, now sharing a border with East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), faced an immediate influx of refugees, communal tensions, and disruptions to trade and cultural ties. The scars of partition were sharp, but the spirit that had carried the region through decades of struggle did not waver. Leaders and citizens alike turned their energies toward shaping their place in a free India.

The role of Assam and the Northeast in India’s freedom struggle was never one of mere spectatorship. From the martyrdom of Maniram Dewan to the eloquence of Ambikagiri Raichoudhury, from the leadership of Gopinath Bordoloi to the youthful defiance of Kanaklata Barua, the region’s contribution was rich in both diversity of approach and unity of purpose. The Brahmaputra carried not just water and silt but also the currents of defiance, hope, and sacrifice, linking tea garden workers, tribal chiefs, students, and poets in a common cause. The hills and valleys of the Northeast echoed with both the gunfire of battle and the verses of poets, with clandestine meetings in bamboo huts and processions through bustling towns.

The freedom struggle here was not an imported ideology echoing from distant cities. It was a lived, local reality—fought in paddy fields and ferry ghats, classrooms and prison cells, markets and monasteries. It was deeply rooted in the land’s historical memory, economic realities, and cultural aspirations. And though the British have long departed, the legacy of that struggle remains, not just in memorials and history books, but in the resilience, cultural pride, and unyielding spirit that continue to define Assam and the Northeast in the Indian imagination.