- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

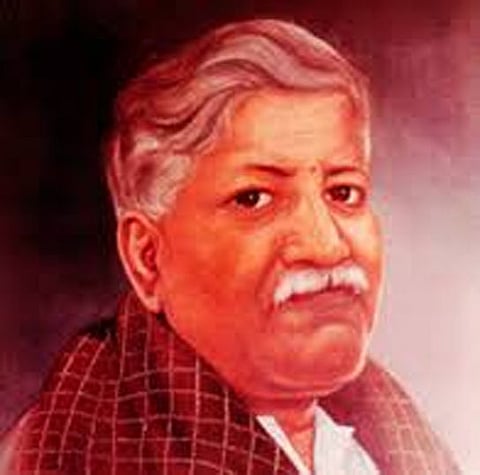

Heramba Nath

(herambanath2222@gmail.com)

There are some lives that cannot be measured merely by the positions they held, the wealth they gathered, or the professional titles that followed their names. They live on because of the light they ignited in others, because of the difference they made to the collective heart of a community, and because of the humanity that radiated from their every act. Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah was one such rare figure whose presence in Assam during a formative period of its history defined what medicine, compassion, and service to society truly meant. To remember him today is not simply to recount a biography, but to hold a mirror to the moral compass of our society, to measure how far we have moved from the ethos he embodied, and to ask ourselves whether his spirit of service can be revived in the turbulent climate of the twenty-first century.

In the story of Assam’s intellectual and cultural awakening, the name of Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah stands tall. His life was not that of a mere physician dispensing medicines and diagnoses. He embodied the very essence of healing, combining scientific knowledge with a heart that could feel the pulse of the suffering masses. The people who came to him for care did not merely encounter a doctor; they encountered a man who saw them as human beings before seeing them as patients. His was the healing touch that assured the frightened, calmed the anxious, and restored dignity to the ailing. If a society can be judged by the doctors it produces, then Dr Borooah’s memory still reminds Assam that medicine is not a marketplace but a moral calling.

The period in which he lived was not an easy one. Assam in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was still grappling with poverty, illiteracy, epidemics, and the many challenges of colonial neglect. The infrastructure of healthcare was fragile, and access to even the most basic services was limited to a privileged few. For the masses, illness was often met with despair, as remedies were scarce and doctors fewer still. It was into this landscape of hardship that Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah stepped in with his firm resolve to treat, to serve, and to uplift. He did not belong to a generation that viewed medical practice as an avenue for profit. Rather, he saw it as a sacred trust, a form of social duty that bound him to his people.

It is necessary to pause here and reflect on what made him unique in that environment. Medical knowledge can be acquired through study, but compassion cannot be purchased in books. The distinction between the ordinary doctor and the extraordinary healer lies not in academic degrees but in the ability to see suffering as one’s own. Dr Borooah’s greatness was not in his technical expertise alone, though by the standards of his time he was certainly well-trained and accomplished. His greatness lay in his moral vision, in his ability to ensure that no person who came to him left uncared for, no matter how poor, how powerless, or how marginalised. In this sense, he became a symbol of medical democracy, treating each life with the same dignity, offering the same dedication whether it was a wealthy household or a destitute peasant.

The humanitarianism that guided him was not accidental. It was rooted in the Assamese cultural ethos, where service, humility, and respect for human dignity were woven into social life. The Assamese bhakti tradition, enriched by the teachings of Srimanta Sankardeva, emphasised compassion, equality, and service as spiritual duties. Dr Borooah’s medical practice reflected these values in action. To treat a patient for him was not only a scientific responsibility but also a moral one. Each consultation was a form of prayer, each prescription a gesture of social solidarity. For those who had lost faith in the indifferent systems of governance or the exploitative forces of colonialism, his presence was like a reassurance that humanity still had protectors.

As we reflect on his life today, more than a century later, we are compelled to ask whether we have been faithful to his example. The medical profession in contemporary India, including Assam, has grown enormously in technical sophistication. Super-speciality hospitals, advanced diagnostic laboratories, robotic surgeries, and artificial intelligence in medicine are now part of the landscape. But alongside these advancements has come a troubling phenomenon—the commercialisation of healthcare. The hospital bed is often allocated not on the basis of need but on the basis of ability to pay. The poor patient, once comforted by doctors like Dr Borooah, today feels abandoned in a labyrinth of bills, corporate interests, and bureaucratic indifference. In such a context, remembering his humanitarian approach is not nostalgia; it is an urgent ethical necessity.

Dr Borooah’s humanitarianism also has to be viewed in the larger canvas of Assam’s intellectual tradition. His generation witnessed a remarkable flowering of reformist thought, educational awakening, and cultural renaissance. Alongside literary stalwarts, social reformers, and educators, figures like Dr Borooah ensured that the intellectual awakening did not remain confined to books and classrooms but entered the everyday lives of people. By serving as a physician of the poor, he ensured that the body of Assam, not only the mind, was healed. This holistic vision of development—where education, culture, and health all advanced hand in hand—remains an enduring lesson for our times.

When patients came to his chamber, they were greeted not with the mechanical indifference of today’s crowded clinics but with warmth and assurance. Testimonies from his time narrate how people felt at ease in his presence, as though the burden of their illness was already lighter. This was because he did not separate the disease from the person. He knew that healing was not only about prescribing a drug but also about instilling hope. He would listen patiently to their anxieties, offer words of encouragement, and treat them as fellow human beings worthy of care. To the poor, who could not afford treatment, he often extended his services freely, guided by the conviction that illness should never be allowed to deepen inequality.

In an age where social media celebrates celebrities and the cult of wealth, it may appear old-fashioned to speak of selfless service. But the truth is that societies cannot survive without such examples. A nation is not sustained only by its armies, parliaments, and industries; it is sustained by the invisible kindness of those who serve without seeking applause. Dr Borooah’s life stands as a testimony to this truth. He did not seek fame, yet his memory is enshrined because the people whose lives he touched carried his story forward. In the lanes of Guwahati, in the conversations of families, in the oral histories of villages, his name was spoken with respect because it represented hope in a world of uncertainty.

The importance of such a legacy becomes clearer when we look at the challenges Assam faces today. The health sector in the state continues to be strained, with shortages of doctors, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access in rural areas. The dream of universal healthcare remains distant. In such a situation, the invocation of Dr Borooah’s life is not a sentimental indulgence but a necessary reminder of the ideals that must guide us forward. If he could practise medicine with humanity in times when resources were scarce, what excuse do we have today, with far greater means at our disposal, to neglect compassion? The technology of healing has advanced, but has the morality of healing advanced as well? This is the haunting question his legacy poses to us.

To describe him as a humanitarian doctor is not to use a decorative phrase but to recognise a truth deeply woven into his daily practice. He was human before he was a doctor, and that is why he was a great doctor. His example compels us to ask whether we view patients as statistics or as souls, whether we treat them as bodies to be repaired or as lives to be dignified. Medicine in its truest form is not merely a science; it is also an art and a philosophy. It is the art of empathy, the philosophy of service, and the science of healing combined into one vocation. Dr Borooah’s life embodied this triad in a way that remains unmatched.

If we stretch our imagination further, we realise that he was not merely a physician of individuals but a healer of society itself. In every poor patient he treated freely, he challenged the inequality of his times. In every gesture of kindness, he resisted the commodification of human life. In every act of service, he affirmed the dignity of the marginalised. He was, in this sense, a quiet revolutionary, whose revolution was not waged with slogans or marches, but with a stethoscope, a prescription pad, and, above all, a compassionate heart. His silent revolution did not overthrow empires, but it built something far more enduring: trust between people and the medical profession.

As Assam grows and modernises, with its bustling cities, its ambitious youth, and its expanding institutions, the risk is that we may forget these silent revolutionaries. We may measure progress only in terms of GDP, infrastructure, and technological indices, forgetting that the real measure of civilisation is the extent to which it protects its weakest. In invoking the memory of Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah, we remind ourselves that the true index of progress is compassion. The day the poor feel abandoned in hospitals, the day doctors see patients only as consumers, and the day healing becomes indistinguishable from commerce is the day we will have betrayed his legacy.

His story, therefore, has to be retold not merely as a biography but as a parable for our times. It tells us that the nobility of medicine is inseparable from the nobility of the heart, that technical skill without moral commitment is empty, and that the true measure of a doctor is not the wealth he accumulates but the lives he restores. It reminds young medical students that to don the white coat is to shoulder a responsibility that transcends personal ambition. It inspires citizens to demand from their healthcare system not only efficiency but also humanity. It calls upon governments to remember that investment in health is not expenditure but a moral obligation.

Perhaps the greatest tribute to him is that his name continues to inspire institutions in Assam. The very existence of the Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah Cancer Institute in Guwahati is not only a functional medical facility but also a living memorial to his spirit. Every patient who walks into its halls, every life saved in its wards, and every family comforted by its services adds another chapter to his legacy. It is fitting that a man who stood for humanity in medicine should have his name associated with an institution that continues the fight against one of the most formidable diseases of our age. But even this institutional recognition is not enough if we forget the philosophy that underpinned his life. Names on buildings may fade in memory, but values lived in practice endure.

The life of Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah is therefore not a closed chapter in history but an open invitation to every generation. It invites us to reflect on the meaning of service, the value of humility, and the centrality of compassion in public life. It challenges us to measure our progress not only by skyscrapers and highways but by the warmth in our hospitals, the accessibility of our clinics, and the trust between doctors and patients. It calls upon us to revive the lost art of listening, of caring, of treating not only diseases but also the fears and anxieties that come with them. It is a call we cannot afford to ignore, for the health of society is built upon the health of its conscience.

When the pages of history record the lives that defined Assam, Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah’s name will always shine brightly. He was not a man of power, yet he empowered the weak. He was not a man of wealth, yet he enriched the poor. He was not a man of political authority, yet he exercised a moral authority that outlived the politicians of his time. His life is a reminder that true greatness is not about domination but about service, not about self-promotion but about selflessness, not about ruling others but about healing them.

As we reflect upon his journey today, we are left with a profound truth: the real doctors of society are not only those who cure diseases but also those who restore faith in humanity. Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah was one such doctor. His memory is not only a legacy to be honoured but also a responsibility to be carried forward. Every generation of doctors, policymakers, and citizens must ask: are we worthy of his example? If we answer this honestly, then his life will not remain a story of the past but will become a guiding light for the future.

In remembering him, we remember not only an individual but a moral ideal. His life speaks across time, reminding us that humanity is the greatest medicine, that compassion is the most powerful drug, and that service is the noblest cure. Assam was fortunate to have him, and India is fortunate to inherit his legacy. The task before us now is to ensure that his humanitarian spirit does not fade into the pages of history but continues to inspire every act of healing, every institution of care, and every heart that beats for the suffering of others.

Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah remains, in the deepest sense of the word, a doctor of humanity.