- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Dr. Tazid Ali

(Professor, Department of Mathematics,

Dibrugarh University. email: tazidali@yahoo.com)

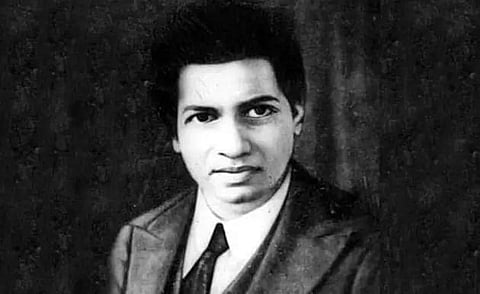

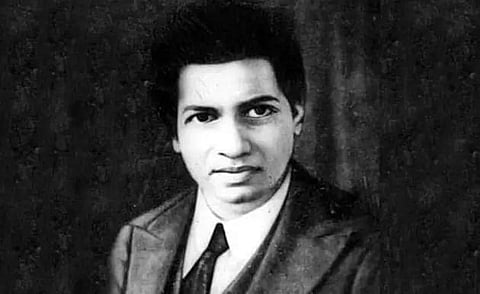

Srinivasa Ramanujan Iyengar is considered to be the greatest Indian Mathematician. Born on 22 December 1887 in Erode, Tamil Nadu, he belonged to a very poor family. He showed his mathematical talent from a very early age. When he was just 12 years of age, he came across a text on Trigonometry by S.L. Loney and within the next year he completely mastered the whole book. At the age of sixteen, he received from a senior student George Carr's Synopsis of elementary results on pure and applied mathematics. This was a two-volume encyclopaedia containing more than six thousand results on different branches of mathematics. Ramanujan could not only work out all the theorems in the book but derived some new results. While at school, one day when the class teacher was explaining the rule of division with an example of the distribution of fruits among classmates, Ramanujan asked a silly looking but deep mathematical question: If no fruits are divided among no students, how many fruits (s) each student would get? He was referring to a very subtle concept of division of zero by zero! Ramanujan's approach to mathematics was unconventional. Most of his results were without proof and even where proofs are given, they lack mathematical rigour. This is basically because he had no formal training or education in mathematics. Because of his extreme poverty, he could not afford papers and hence did his problems in a slate. After the calculation, he simply used to jolt down the results in his notebook. Ramanujan tried to contact mathematicians in Bombay to discuss his mathematical results. But his work could hardly be appreciated or assessed by anyone. Narayana Iyer, who was then the Chief Accountant of Port Trust Madras and himself an active worker on mathematics, suggested Ramanujan write to mathematicians of England. He wrote to three Mathematicians, two of them did not respond. The third was G. H. Hardy, Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. Initially, Hardy looked at the 120 mathematical results of Ramanujan with distaste. But then he called his fellow mathematician J. E. Littlewood and both sat to verify the results. Soon they realized the genius of the Indian boy. Hardy remarked: I have never seen anything like them before. The theorems had to be true because no one had the imagination to invent them. The year was 1913 and it was the turning point not only in the life of Ramanujan but also in the history of Mathematics. Hardy then invited Ramanujan to Cambridge. He left for England in March 1914. The period of stay at Cambridge was a super activity period for Ramanujan. There he wrote in total 32 research papers.

Ramanujan received a B.A. degree in 1916 from Cambridge University. In 1917 he was elected to the London Mathematical Society and in the next year, he was inducted as a fellow of the Royal Society of London. The same year he also became a Fellow of the Trinity College, Cambridge; the first Indian to be so honoured.

Ramanujan was very fond of numbers. He always explored beauty and patterns in numbers. In England, once Ramanujan was admitted to a hospital due to some illness. Hardy visited him one day. Hardy mentioned that the number of the Taxi on which he travelled to the hospital was 1729 and that it seemed to be a very dull number to him. Ramanujan thought for a moment and replied that the number is very interesting. It is the smallest number that can be expressed as the sum of two cubes in two different ways. This number is popularly known as the Ramanujan number.

After returning from England during the last year of his life (1919-1920) Ramanujan developed some new formulas. After Ramanujan's death his wife handed over those notes to Madras University and from there it was later sent to British mathematician G. N. Watson. Watson did a lot of research on these results. After Watson's death, these notes were handed over to the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1976, while searching through the papers of the late G.N. Watson at Trinity College, Cambridge, American mathematician George Andrew found those 138 pages of Ramanujan's work. These notes are referred to as the 'Lost Notebook' of Ramanujan. It contained more than 600 formulas developed by Ramanujan. No proof was provided in the notes. Later George Andrew along with another American mathematician B. C. Berndt published several books wherein they proved many formulas of Ramanujan as given in the notebook. The proof required some of the most sophisticated mathematical tools like complex analysis and Galois Theory. As Ramanujan was not familiar with these tools, it appears that he must have obtained his results by some alternative and profound approach. Berndt expressed his opinion on the notebook as The discovery of this 'Lost Notebook' caused as much stir in the mathematical world as Beethoven's tenth symphony in the world of classical music.

In 1962, the 75th birth anniversary year, the Government of India issued a postage stamp in honour of this mathematical genius. And in 2011 the Government of India decided to celebrate 22nd December Ramanujan's birthday as the National Mathematics Day every year in recognition of his contribution to mathematics.