- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Himangshu Ranjan Bhuyan

(hrbhuyancolumnist@gmail.com)

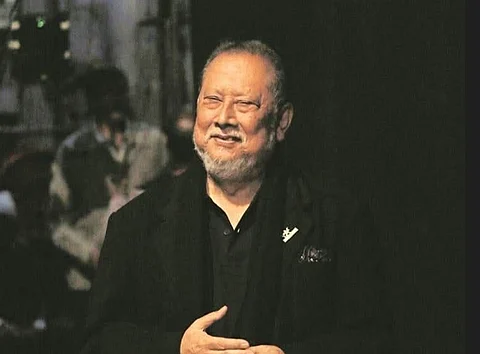

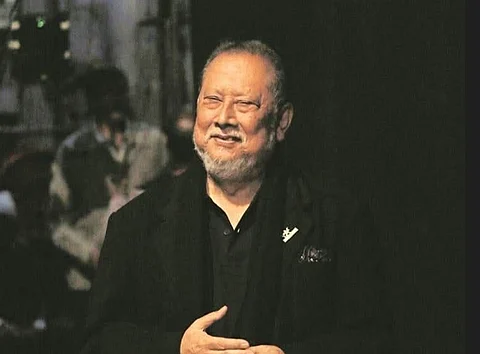

The recent passing of Ratan Thiyam marks not only the departure of a distinguished theatre maestro but also the fading of an epoch that revolutionised Indian dramatic arts. In the legacy of cultural luminaries, a few names shine with the incandescent brilliance of Ratan Thiyam—an artiste, playwright, director, and philosopher whose creative genius etched new contours into the landscape of Indian theatre. Hailing from the small yet culturally rich northeastern state of Manipur, Ratan Thiyam was far more than a dramatist—he was a philosopher of performance, a craftsman of narrative traditions, and a relentless seeker of truth through theatrical language. His demise leaves a void that cannot be filled merely by accolades or retrospectives; it invites deep introspection on what it means to create art that engages with society, philosophy, tradition, and the inner human condition.

Born in 1948 in Imphal to a family rooted in the traditional arts, Thiyam was drawn early to Manipuri classical forms, but it was his education at the National School of Drama under the mentorship of Ebrahim Alkazi that refined his instincts into disciplined brilliance. From that crucible of experimentation, Thiyam emerged not just as a graduate but as a revolutionary voice who would soon redefine Indian theatre aesthetics. In 1976, he founded the Chorus Repertory Theatre in the heart of Manipur, an act that was as much a political statement as an artistic venture. At a time when Indian theatre largely revolved around the metropolises, Thiyam’s decision to build a global theatre movement from the fringes of India was both daring and transformative. This move symbolised his commitment to decentralisation—not only geographically but also thematically and ideologically.

What made Ratan Thiyam’s work exceptional was not merely the content of his plays but the method of their realisation. His productions, whether rooted in classical Indian epics or adapted from modern texts, pulsated with spiritual, philosophical, and political undertones. He merged traditional Manipuri art forms like Thang-Ta, Ras Lila, and Sankirtana with contemporary staging techniques, creating a language that was both ancient and shockingly modern. It was this unique grammar of performance that allowed his works like Chakravyuha, Andha Yug, Uttar Priyadarshi, Ritusamharam, and Lengshonnei to transcend cultural and linguistic boundaries. Each production was not just a performance but an experience—a ritual, a meditation, and a mirror held to society and the self.

His seminal production, Chakravyuha, drawn from the Mahabharata, was a monumental allegory about the entrapment of innocence in political machinations. It carried the weight of the Manipuri youth’s plight—lost in the labyrinth of insurgency, state violence, and identity crisis. It was more than a play; it was a lament, a question, and a protest. His Uttar Priyadarshi, based on Hindi playwright Agyeya’s interpretation of Ashoka’s spiritual transformation, was not just a historical reconstruction but a philosophical inquiry into guilt, repentance, and redemption. With these works, Thiyam established theatre as a vehicle of social commentary and moral philosophy, far removed from mere entertainment.

Central to Ratan Thiyam’s artistic temperament was his unwavering belief that art must resonate with the moral pulse of its time. In a region frequently torn by political unrest and socio-cultural marginalisation, he transformed theatre into an instrument of resistance, healing, and identity formation. He once returned the prestigious Padma Shri award as a gesture of protest against violence in Manipur—an act that exemplified his artistic integrity and moral courage. For Thiyam, theatre was not confined to proscenium boundaries; it was a living discourse that interrogated power, injustice, and the erosion of values.

His visual aesthetics were marked by minimalism and grandeur in equal measure. The stage in a Thiyam production was often sparse yet laden with symbolic weight. A single beam of light, a circular platform, the rhythmic chanting of monks, or the stillness of actors in meditative postures created a poetic landscape. His training in visual arts and music infused his direction with a painter’s eye and a musician’s rhythm. The result was a synesthetic experience where text, movement, light, and sound became one integrated vocabulary of expression.

As a cultural leader, Thiyam played critical institutional roles. He served as the Director of the National School of Drama and later as Chairperson of the institution, bringing with him the rigour of pedagogy and the depth of artistic inquiry. Under his stewardship, NSD expanded its reach beyond urban India, touching tribal and vernacular traditions, thereby democratising the theatre ecosystem. He was also closely associated with the Sangeet Natak Akademi and other prestigious cultural platforms, yet he never lost touch with the grassroots. His work with young theatre practitioners in Manipur and across India kept his artistic vision fertile and future-orientated.

While Ratan Thiyam’s oeuvre remained deeply rooted in Indic philosophical traditions, he was not insular. He absorbed the global while retaining the local. His works travelled to Europe, the Americas, Japan, and Southeast Asia, where they were greeted with critical acclaim and scholarly attention. Yet, he never performed for the West’s gaze; he performed with a deep conviction in the universality of Indian theatre’s spiritual and philosophical heritage. Whether drawing on Kalidasa, Sophocles, Tagore, or Jean Anouilh, Thiyam’s dramaturgy was rooted in the belief that great art transcends the binaries of East and West, ancient and modern, and sacred and profane.

Thematically, his plays constantly returned to questions of moral conflict, human suffering, cosmic balance, and spiritual awakening. His protagonists, drawn from mythology or contemporary life, were often caught in dilemmas that reflected the collective angst of societies in transition. They were symbols, not merely characters. Through them, he explored violence and non-violence, silence and speech, and action and contemplation. This moral duality lay at the heart of his artistic vision.

Importantly, Ratan Thiyam’s contributions extended beyond stage productions. His theoretical writings, design innovations, musical compositions, and painterly experiments enriched Indian theatre’s vocabulary in multidimensional ways. He envisioned theatre not as a single-medium craft but as a holistic cultural practice. He insisted that a theatre artist must be a philosopher, technician, and activist rolled into one—a standard he lived up to with rare consistency.

His influence on Indian theatre is incalculable. Younger directors from across regions and languages—be it Kerala, Bengal, Maharashtra, or Assam—looked up to Thiyam for both inspiration and guidance. His Chorus Repertory Theatre in Imphal became a pilgrimage site for aspiring performers, directors, and dramaturgs. Festivals like Bharat Rang Mahotsav frequently honoured his work, yet no festival could quite contain the range of his vision. He was not a mainstream celebrity but a subterranean force who shaped Indian theatre’s spiritual and aesthetic backbone.

At a time when theatre in India increasingly finds itself caught between populism and commercialism, Ratan Thiyam’s life and work remind us of theatre’s sacred obligation—to illuminate, to interrogate, and to transform. His productions never catered to applause but sought to awaken audiences into reflection. In the echoing silences of his scenes, one heard not absence but the presence of something deeper—perhaps the conscience of an artist listening to the soul of a nation.

In the aftermath of his passing, the tributes pouring in from cultural institutions, fellow artists, politicians, and international communities are a testament to the depth and breadth of his legacy. Yet, even as the nation mourns, it must do more than offer ceremonial praise. It must institutionalise his vision through theatre fellowships, documentation of his archives, translation of his scripts, and integration of his techniques into performance curricula. His life’s work should be made accessible not only to elite theatre circles but also to rural and marginalised communities, for whom theatre can still be a source of healing and identity.

Ratan Thiyam believed in the cyclical nature of time and the eternal return of values and aesthetics. His death, therefore, should not be seen as an end but as a karmic pause—inviting future generations to carry forward his legacy with integrity and innovation. The flames of ritual he lit on the stages of Imphal, the moral questions he posed through his characters, and the silences he choreographed like music—all these must now become guiding lights for Indian culture. In a world increasingly fragmented by violence, hyper-nationalism, and moral apathy, the theatre of Ratan Thiyam stands as a luminous counterpoint—a place where the soul is not only seen but heard. His stage was a temple, his actors were seekers, and his audience was invited to partake in a ritual of awakening. Such was the magnitude of his art and the nobility of his intent.

Ratan Thiyam may no longer walk among us, but his vision marches on—in the footsteps of barefoot actors on village stages, in the flicker of oil lamps lighting sacred narratives, and in the collective memory of a culture that still believes in the redemptive power of theatre. Let us not forget the man who gave India not just plays, but paradigms. Let us honour him not just in words, but in the continuance of a tradition he so lovingly and courageously nurtured.