- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

From Pragjyotishpur to Kamrup

Ayush Mazumder

(ayushmazumder660@gmail.com)

In the sacred land of India, there are a handful of places that blend the notion of myth and history effortlessly as the ancient land of modern day Assam – initially known as Pragjyotishpur in the epics and as Kamrup in the medieval scriptures. This particular land was not just a mere political corner but was a pedestal of cosmic stage where the gods, demons and the humans acted together in the theatre of creation, conquest and devotion. Two of the most revered ancient texts of Assam are Kalika Puran and Yogini Tantra that pave a path of how myths preserved in the scripts shaped Assam’s historical memory. Pragjyotishpur means “The City of Eastern Light”. In the epic Mahabharat, this region appears to be ruled by legendary King Narak , the son born from the union of Varahadev and Bhudevi. It could be traced from the eleventh century text Kalika Puran that elaborates his origin: bhumer garbhasamutpanno narako nama daityaja? (Born from the womb of the Earth was the demon Naraka). — Kalika Purana, 38.11. Narak or popularly known as Narakasur is portrayed as a son of divine intervention and a political architect who has been credited with fortification of Pragjyotishpur and incepting the worship of Goddess Kamakhya. These legends put forward Assam in the pages of ancient Indian history of state formation and ruling dynasties asserting legitimacy through divine theory of kingship.

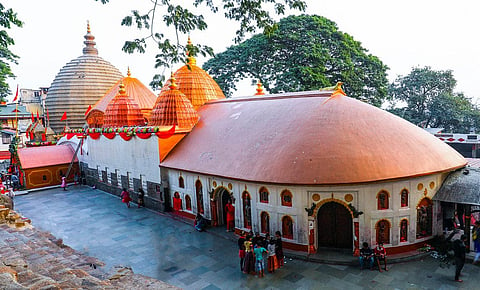

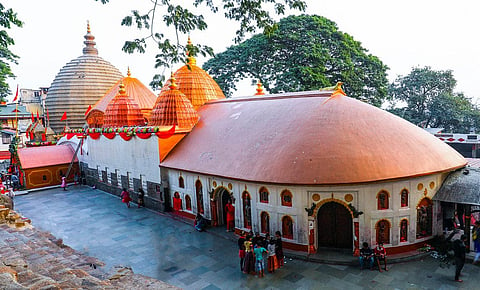

In the literature of the early medieval period, Pragjyotishpur gives space to Kamrup in the inscriptions and religious texts. The seventeenth century text Yogini Tantra describes Kamrup as one of the four significant pithas, where the yoni of Sati fell after the Shiva’s cosmic dance of grief: “kamarupa? mahapi?ha? yatra yoni? patita pura” (Kamarupa is the great pitha where once the yoni fell.) — Yogini Tantra, I.32. This fables transcends Assam into the cosmic womb, a holy land where creation is heavenly rejuvenated. The change in the name also points out to the political shifts from the ancient dynasties claiming mythical descent to the medieval rulers walking along the routes of rise of Shaktism. The epicentre of all the narratives is the shrine of Goddess Kamakhya situated on the top of Nilachal Hill. An entire chapter in the Kalika Puran has been devoted to the sanctity, rituals of fertility, cosmic order and tantric practices. With the absence of any anthropomorphic idols, the garbagriha is enshrined with a stone cleft, boldly symbolizing creation as sacred through the yoni of the Goddess. The annual Ambubachi Mela, which is marked by the Goddess’s menstrual

Period, is being still celebrated which is being linked by the Kalika Puran to the agricultural prosperity and the chakra of renewal of life, turning it into a both spiritual and seasonal calendar for the people.

Shakta scriptures from Assam acts more than the narration of myths, they encode a political theology. The lineage of Naraka and Bhagadutta in the Mahabharat and Kalika Puran designs kingship as something divinely ordained through the blessings of the Goddess. The Yogini Tantra has portrayed the rulers as an ideal guardian of Dharma by maintaining the worship of the Goddess and protecting the sacred space. In the copperplate inscriptions of the seventh century King Bhaskarvarman, describes how kings patronized the religious institutions. The rulers aligned themselves with Kamakhya and asserted their political subjugation ensuring their dominating stature while entangling the ideas of divine intervention.

In the stories of the Goddess Shakti, it’s quite difficult to speak about the origin and the end of the ancient myths. Eminent historians such as Romila Thapar and Upinder Singh speak about the old days where people didn't really distinguish myths from the world of history. Scared stories weren't falsified rather it was carved by the people for their remembrance and asserting the importance to their past based on their existing culture. For the instance, the account stated by Kalika Puran of Narakasur’s capital aligns slackly with the archeological discoveries near the present day Guwahati, showcasing the classic example of myth preserved in a memory of early urban settlements. Similarly the detailed mapping of Kamrupa in the Yogini Tantra overlaps the actual geography of the place creating a rift of blurred lines between religious cartography and political territory. Sites such as Ambari and Dah Parbatiya were excavated which revealed material cultures, sculptural fragments which dates between 6th-10th centuries CE, the period when Shakta literature was flourishing. While these sites are not exactly an evidence of certain folklores nevertheless they provide a tangible conception in which such myths could have emerged and circulated. Like the Dah Parbatia lintel depicting the Gajalakshmi may reflect a larger goddess worship tradition which later has been codified in to a distinct Shakta framework. Here literature and archeology present themselves as twin witnesses to Assam’s multilayered past.

The significance of Kamarupa as a Shaktipeeth has put Assam in a scared landscape that stretched from Jalandhar in the north to Kanyakumari in the south. The pilgrimage routes mentioned in the Yogini Tantra, has connected Kamakhya with other Shakta centres such as Ujjain and Kanchi. This inclusion into the wider Shakta network may explain why Shaktism in Assam has grown into a distinctive synthesis of tribal goddess worship, sanskritic ritual and esoteric tantra.

Even in the present day, the rituals of the Kamakhya temple echoes of the practices written in the Kalika Puran and Yogini Tantra. The offering of the symbolic cloth during Ambubachi, the chanting of the Goddess invoking as Mahamaya and the belief that she is the true guardian of this land, all these speaks to a continuous cycle where ancient scriptures are not museum relics but living objects enacted daily. In the reconstruction of the Assam’s ancient past through Shakta literature we are not merely cataloguing myths; we are tracing a cultural memory that has provided guidance to identity, politics and spirituality for over centuries. The overlap of the fables, myths, folklores and history in the Kalika Puran and Yogini Tantra is not a flawed concept but a feature which has to be understood as a reminder that in the Indian imagination the past is not a closed book, but a living presence. Kamrupa, a place where history wears the face of the goddess and the goddess,the face of the land.

References

n Kalika Purana (ed. B.Bhattacharya, 1935)

n Yogini Tantra (trans. P.T.Tripathi, 1965)

n Bhuyan, S.K. The Comprehensive History of Assam, Vol. 1, 1990.

n Lahiri, Nayanjot. Pre-Ahom Assam: Studies in the Inscriptions of Assam between the Fifth and the Thirteenth Centuries.

n Thapar, Romila. The Past Before Us, 2013.

n Singh, Upinder. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India, 2008.