- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

Neelim Akash Kashyap

(neelimassam@gmail.com)

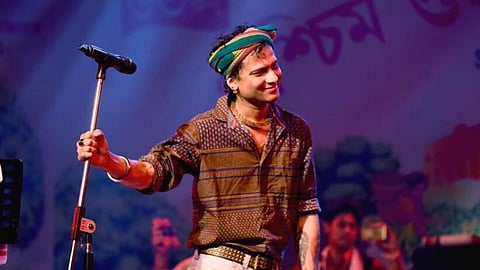

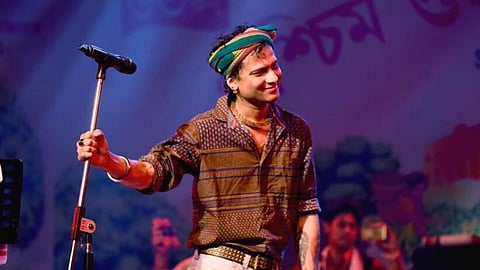

In the weeks following the passing of Zubeen Garg, a number of books on his life and legacy have resurfaced or been newly published, drawing renewed public attention. Some are reprints of earlier works; others are recent additions. Readers have shown genuine interest, but alongside this has emerged a troubling refrain on social media—the insinuation that such publications are motivated by ‘business’.

The writing of books after the death of a major cultural figure is neither unusual nor unethical. Literature has always responded to loss by documenting, interpreting, and remembering. It is through books that future generations will come to understand not only Zubeen Garg’s music and films but also his ideas, contradictions, and cultural significance. The question worth asking is not when a book is written, but how—and with what sense of responsibility. Accuracy, sensitivity, and readability should be the true measures of merit.

Preserving Zubeen Garg’s legacy cannot be limited to replaying his songs or revisiting his films. Cultural memory demands documentation. Books offer context, continuity, and reflection—elements that popular consumption alone cannot provide. To dismiss such efforts as commercial exploitation is to misunderstand both literature and the economics of publishing.

The word ‘business’, when applied to books, deserves closer scrutiny. Anyone familiar with the publishing industry knows that authors rarely earn meaningful financial returns. For most writers, literature is not commerce but commitment—a form of sustained intellectual and emotional labour. Those quick to accuse writers of profiteering might ask a simple question: how much does an author actually earn from a book?

It is also important to note that several books now being discussed were written and published years ago. Their renewed visibility reflects delayed public engagement rather than sudden opportunism. If earlier editions took time to sell, the reason was not excess production but limited readership. This belated attention says more about our reading habits than about authorial intent.

The authors who have written on Zubeen Garg include respected literary figures with long-standing commitments to serious writing. It is implausible to suggest that such writers suddenly discovered financial or reputational gain in the aftermath of his death. Even if isolated instances of opportunism exist—as they do in every field—they cannot be used to discredit the broader literary response to loss.

On a personal note, I had planned a novel on Zubeen Garg during his lifetime and had discussed it with a publisher. His sudden passing did not create that intent; it intensified it. Following his death, two novels—’Utha–Jaaga–Xaar Powa’ in Assamese and ‘Tempest over Brahmaputra’ in English, respectively—were written as acts of remembrance. They emerged from prolonged engagement, reflection, and countless sleepless nights. To reduce such work to ‘business’ is to overlook the emotional and intellectual labour behind it.

The fixation on how quickly a book is written—whether in weeks, months, or years—is misplaced. Time alone does not determine depth or integrity. What matters is whether a work is truthful, coherent, and meaningful. Criticism, when necessary, should focus on these aspects, not on speculative motives. It should also be offered with intellectual restraint rather than reflexive cynicism.

Zubeen Garg once observed that “a gamosa cannot save a bookless nation.” The remark feels particularly relevant today. Bookshops are closing, readership is shrinking, and serious writing often meets suspicion instead of engagement. In such a climate, discouraging books—especially those that attempt to preserve cultural memory—is counterproductive.

People remember Zubeen Garg in different ways. Some sing his songs. Some revisit his films. Some carry him in emotion and silence. Writers remember him through words. These are not competing acts of remembrance; they are complementary. A living cultural legacy requires multiple forms of engagement to coexist.

If the aim is to carry Zubeen Garg forward in time and introduce him to future generations, we must encourage careful documentation, responsible writing, and thoughtful reading. What is needed is not blanket accusation but discerning critique; not suspicion, but engagement. At its best, literature is not business—it is remembrance.

(The author can be reached at neelimassam@gmail.com)