- Home

- Live Blog

- Breaking News

- Top Headlines

- Cities

- NE News

- Sentinel Media

- Sports

- Education

- Jobs

CORRESPONDENT

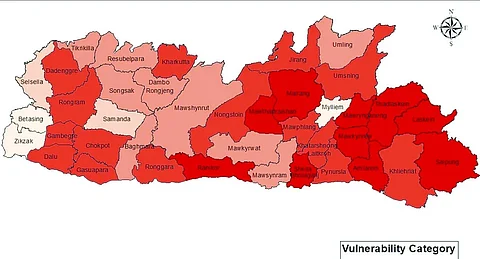

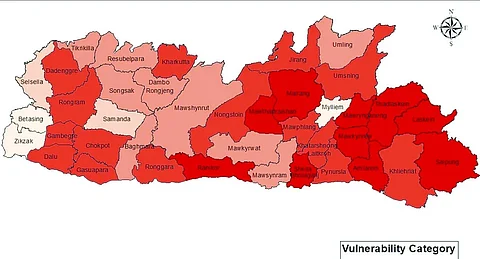

SHILLONG: In a major revelation that cuts to the core of Meghalaya’s environmental fragility, a pioneering climate vulnerability study has found that 25 out of 39 Community and Rural Development (C&RD) Blocks are grappling with high or very high risk from climate change—laying bare urgent policy gaps across one of India’s most ecologically delicate states. Conducted by the Meghalaya Climate Change Centre (MCCC), the study titled Integrated Climate Vulnerability Assessment of Meghalaya at Block Level was recently published in Discover Sustainability, a peer-reviewed journal under the Springer Nature Group. This landmark analysis, based on the nationally adopted framework of the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE), offers a sharper lens into climate risk zones through block-specific data—an often-overlooked scale in mainstream assessments.

“This study presents a novel, block-level climate vulnerability assessment for Meghalaya based on the common framework developed under the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE). By integrating biophysical and socio-economic indicators through a tiered, top-down approach, the work refines vulnerability evaluation to a finer spatial resolution,” the report states.

The findings underscore Meghalaya’s acute vulnerability due to its heavy reliance on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, water, and forestry. Sharing a 443 km international border with Bangladesh and surrounded by Assam, the largely rural and hilly terrain of Meghalaya makes it particularly prone to climate-induced disruptions and extreme weather events.

The assessment measured vulnerability across three dimensions—exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity—and found that Thadlaskein block in West Jaintia Hills is the most vulnerable, followed by Ranikor and Laskein, while Zikzak, Betasing, and Mylliem emerged as the least vulnerable.

Key structural weaknesses contributing to this vulnerability include low household incomes, weak rural infrastructure, scarce forest cover, and poor access to institutional credit. The study found that over 70% of households in 32 blocks earn less than Rs 5,000 per month, placing them in a severely sensitive bracket with minimal capacity to adapt. Alarmingly, less than 2% of households in most blocks hold a Kisan Credit Card with a credit limit of Rs 50,000 or more—an essential tool for smallholder resilience.

The state’s irrigation coverage further aggravates the situation. Only 14.45% of net sown area is irrigated, with 29 out of 39 blocks reporting irrigation levels below 20%. This leaves agriculture, already highly vulnerable to erratic rainfall, further exposed to climate shocks.

Public service distribution was found to be deeply uneven. “Anganwadi centres, which are critical for maternal and child health, are unevenly distributed. In some cases, the gap between the most and least served blocks is as wide as 145 centres,” the report points out. Similarly, very few blocks have forest cover exceeding 10 sq km per 1,000 rural residents, a traditional pillar of community resilience.

Policy recommendations from the study include enhancing financial inclusion by widening rural credit access, improving rural infrastructure such as irrigation and Anganwadi centres, and investing in community-led natural resource management. The researchers stress the need for participatory, data-driven planning models rooted in local contexts.

“Our findings—revealing that 25 out of 39 blocks fall under high or very high vulnerability—highlight that local-scale analyses can uncover critical disparities that more aggregated assessments might miss. The identification of key drivers (e.g., insufficient financial access, inadequate public infrastructure, and scarce natural resources) directs policymakers to prioritise interventions that improve adaptive capacities,” the authors stated.

While acknowledging that the current assessment relies on secondary data that may be dated, the researchers call for follow-up studies based on primary fieldwork and direct community engagement. They also advocate for broader regional collaboration within the Indian Himalayan Region to address shared vulnerabilities and shape holistic adaptation strategies.

Also Read: Meghalaya Issues Warning to Unrecognised Schools

Also Watch: